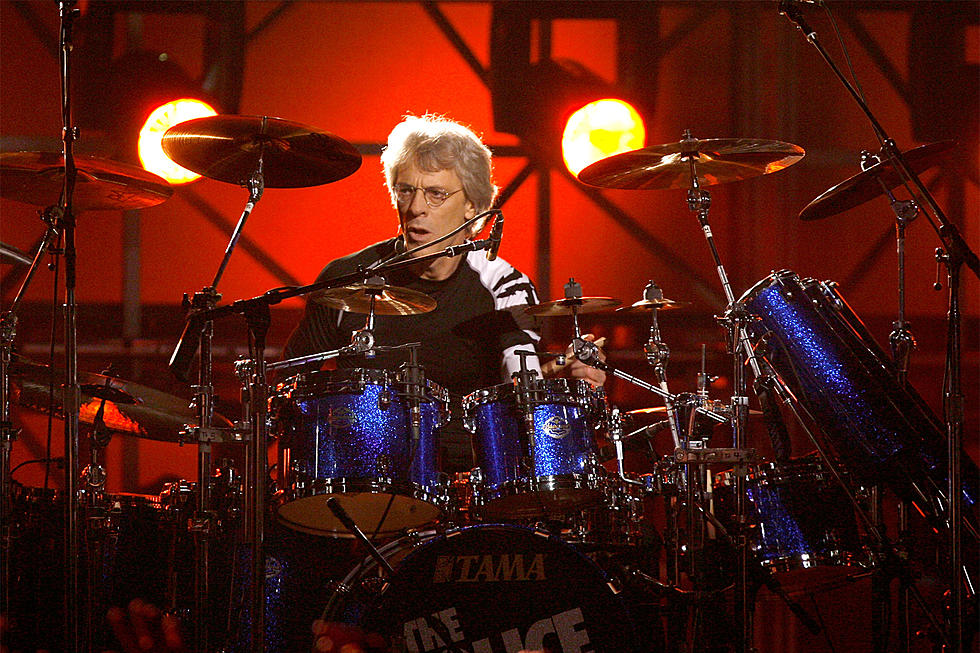

Why Stewart Copeland Took a ‘Deranged’ Approach to His New Tour: Exclusive Interview

Police drummer Stewart Copeland has never been one to walk the expected path.

Even as his time with the influential English rock group began to wind down in the early '80s, he was already building a lengthy list of new creative excursions. He had been scoring for both television and film, working on 1983’s Rumble Fish, 1987’s Wall Street and Talk Radio, while also composing the theme for 1985’s TV thriller The Equalizer. In 1989, he took a shot at opera with Holy Blood and Crescent Moon.

Copeland has continued working in a number of different directions, including further opera projects. The pandemic period was especially productive as he finished one opera and wrote another during his year away from the road.

Now, branching off of his 2006 Police documentary, Everyone Stares, Copeland has returned to his former group’s catalog, creating “derangements” that he’ll perform with orchestras starting Aug. 27 in San Diego. Police Deranged for Orchestra will make additional stops this fall in Cleveland, Buffalo, Atlanta and Los Angeles, with further dates notched for 2022 in Portland, Nashville and Amsterdam.

The drummer joined us recently to discuss how things came together for his upcoming trek, which also features Paul McCartney guitarist Rusty Anderson, Copeland's onetime bandmate in Animal Logic.

How does your style of drumming work with an orchestra? Do you have to approach it with more discipline?

Not creative discipline, only physical discipline. I have to be no more than a quarter of the volume that I would be with a rock band. Normally, that discipline would not work on me, because I’m kind of an instinctive creature of nature on the drums!

But in the case of that little violin solo, the violin lady is like 20 feet away from me and I want to hear what she’s playing on her acoustic violin. So that induces me, since I wrote what she’s playing on that acoustic violin, that imposes some discipline on the drummer guy. I’ve learned to play incredibly quietly! The upside of that is that all kinds of [jazz drummer] Joe Morello [of Dave Brubeck fame] technique. You know, real delicate, sensitive, expression on the drums.

I know that sounds oxymoronic or just plain moronic. But it’s true: You play the drums quietly, the little roughs and the little drags, the nuances, the little pushes and stuff like that. Clyde Stubblefield [known for his work with James Brown] played very quietly, [Rolling Stones drummer] Charlie Watts.

There’s a whole load of expression you can get out of a drum set when you just sooth them, tickle them and inspire them with love. [Laughs.] They sound much better. They sound more resonant, more beautiful and have more power when you need it. And the third thing? Nobody gets a headache.

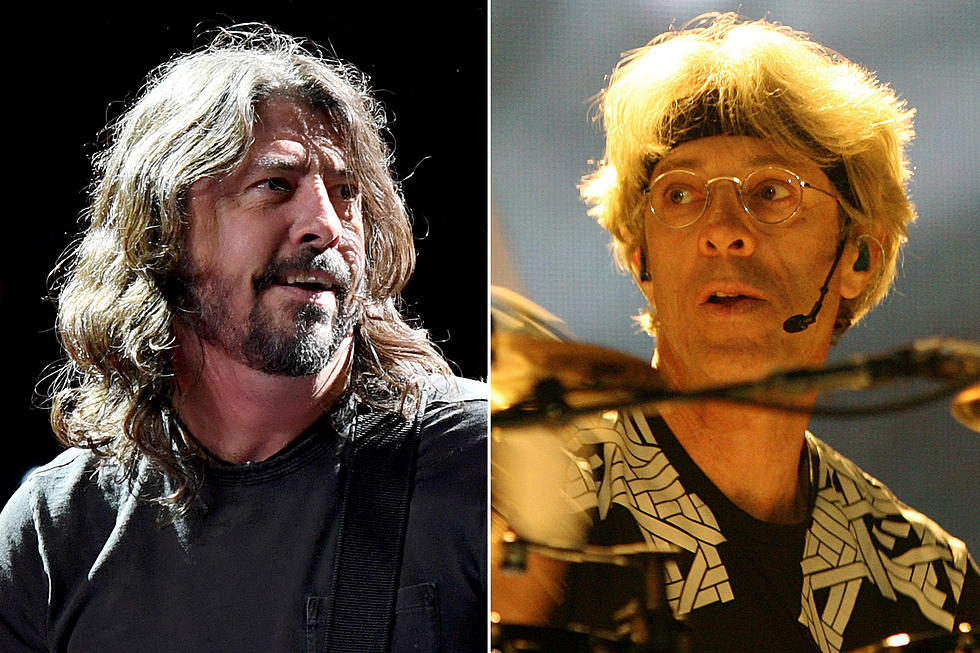

Drummers like yourself and Kenny Aronoff, Dave Grohl, these are all specific players that are known for playing a certain way. Dave Grohl, as an example, is known for being a very loud, intense player. How did you find the space where you needed to be with the orchestra?

Bonding with the music I wrote helps. The actual physical technique is that I practice without headphones. I have little [Yamaha] NS-10 speakers halfway across the room at mid-volume. If I go and play with that, the minute I overdo it, I lose the plot.

It’s taken a long time – actually, years – to get it down to this level of subtle finesse that I can accompany a solo violinist who is 20 feet away. But the technique is pretty simple: Just have your practicing, rehearsing environment, very quiet.

These Police Deranged for Orchestra shows sound like a really cool thing. I love that you have Rusty Anderson on guitar.

Oh, man. He is so great. We played together in a band called Animal Logic 100 years ago [and] we stayed in touch all of these years. We actually meet up on the bike path every Sunday. [Not to talk about music, but] with a couple of other friends. We’re deeply bonded chuckle buddies, but also, he’s a heck of a guitarist.

As an example, at one of our meetings when we were talking about it, he comes over and I said: "Don’t worry about your guitar; we’re just going to talk about the orchestral environment – which is very different from a rock 'n' roll environment." His charts, you know, he’s not a big reader, but he’s going to learn the part. He’ll be, as they say in opera, off book. He’ll just learn it. It’s easy. It’s Police songs, for God’s sake!

He comes over and picks up my 1967 Stratocaster, with the original strings. [Laughs,] He tunes it up and doesn’t even look at the knobs on the amp, nor my pedalboard that I’ve got there for guitarists. He just makes it happen with his fingers. He doesn’t need no pedalboard. He’s not like Mr. Looking for the Sound. He just has it in his fingers.

He makes the guitar sing, no matter what the state of the strings, nor the amp, nor any other factor. He will make that guitar sing beautifully, as he does for Paul McCartney – that’s his day job.

Watch a Promo for 'Police Deranged for Orchestra'

So how did the Police Deranged for Orchestra idea come together?

The derangements came from one direction, the orchestra came from the other direction. For many years now, I’ve been playing concerts with orchestras, my concerto for drums and orchestra, commissioned by the Pittsburgh Symphony.

With the Chicago Symphony, the film that I curated, [1920’s] Ben-Hur, I composed an orchestral score for it. I’ve been around the world playing that show, orchestra, drums and big-ass silent film. As well as, I did a tour in Germany and England with just my film music of various kinds, Rumble Fish, Wall Street, The Equalizer and various other things – and a couple of Police songs that I wrote.

That actually kind of got people’s attention. The Police songs were really well-received. I’m in the classical world and when I play my concerto, Tyrant’s Crush, the other artists on the bill are Ravel, Stravinsky – you know, it’s what they call “core classical.”

All of these big orchestras, in the front office, they also have another division, which is what they call “The Pops.” You know, your John Williams and [stuff that’s] more easily accessible. Not Brahms, not Wagner. So [people in the business] said, "Look, you actually belong on that side of the orchestral world." And you know, I prefer playing my concertos, because it’s all about the music and it’s much deeper. But playing music that people want to hear is really uplifting.

And so I thought, “Screw it, I’ll orchestrate all of these songs that I did not write, but somebody else wrote.” You know, I played them, I loved them and they’ve brought so much beauty into my life. I love these songs. So getting in there and ear-balling what the hey [former Police bandmate] Andy [Summers] was doing on that guitar really reminded me of the genius of my two erstwhile colleagues.

You’re not someone who would just orchestrate these things normally. What has it been like going in and working up the arrangements? How did you approach that?

Okay, that’s where the derangements come in. That happened completely from somewhere else. Back in the day, the first excess money in my pockets, I got a movie camera, Super 8, with sound. I shot the whole rocket ship rise of the Police’s epic voyage. At first, I couldn’t really do anything with the footage, because there’s no negative. Every time you look at it, you scratch it a little bit. So it went back in the shoeboxes. Well, I forgot about that for 20 years. Until they invented computers! Soon after that, they invented cheap memory, where I could download my cheap memories onto hard drives and start carving it up.

The application then was Final Cut Pro, which I don’t use anymore. I’m now on [Adobe] Premiere. I was able to cut a movie and to my surprise, Sundance invited me over to partake of the festival. You know, it actually became a movie. So in service of the movie, obviously, I needed Police music. As a film composer, I’m frustrated that “Roxanne” is such a great song, but right here, where the movie takes a left and goes into [this part], “Roxanne,” the song, does not. So I have to carve the song up to make it serve the film. You know, brutally, as you do as a film composer. The music is in service of the movie. That’s just the philosophy of film composing.

The only purpose for any music at all is to serve the emotional message of a scene. And so, once the scalpel was out – and I’ve got the Pro Tools sessions of all of our original recordings, the multi-tracks and, oh shit, I found all kinds of cool stuff in there! You know, lost guitar solos, strange alternative harmonies that Sting tried out, a lot of live stuff. Because live, when we improvised on stage, they both did amazing things. And gosh, I wish that was on the record.

Well, I found them – and I carved them up. Not all of the songs; some of the songs are like diamonds. You know, “Message in a Bottle” cannot be carved up. There’s only one form of “Message in a Bottle.” So that’s intact. But others, I deeply screwed with them.

What's the one that you're most proud of your carving work on?

“Can’t Stand Losing You” / “Regatta [de Blanc].” I took all kinds of live material, as well as the studio material. I mean, there’s some incredible playing that Andy did on the guitar, which really works in the strings. I was [also] able to take what Sting did vocally – and now, I’ve got three soul sisters on the mic who can take that even further.